Out of Scope: The Untimeliness of the HBS Investigation

When HBS secretly and unilaterally introduced its new research integrity policy in August 2021, after it received allegations against my work, it imposed a provision that speaks to which papers are in scope. From the new policy page 1:

“[The Policy] applies only to allegations of research misconduct that occurred within six years of the date HBS received the allegation, unless: the respondent has continued or renewed an incident of alleged research misconduct through the citation, republication, or other use for the potential benefit of the respondent of the research record in question; or HBS determines that the alleged misconduct would possible have a substantial adverse effect on the health or safety of the public.”

Notice the fundamental rule: There is ordinarily a maximum of six years between the occurrence of the research misconduct and when HBS receives the allegations. Ordinarily, any paper older than that is out of scope and cannot be investigated within the framework of the 2021 policy.

The policy then offers two relevant exceptions to the six-year rule. Since my research doesn’t pertain to health or safety, the second clause is not relevant. That leaves the first exception, in which HBS claims the right to extend that period if a person “continued or renewed [the] alleged research misconduct” through “citation” or “other use” of the research “for the potential benefit of the respondent.”

Let’s examine my papers in light of this rule and its one potentially-relevant exception. As you’ll see, of the four papers where critics alleged problems with my research, three are out of scope according to these rules.

Before diving into the details, I’ll note that the committee investigating me spent literally not a single word on this. They were the first committee ever to apply HBS’ new policy, so they should have been correspondingly careful in figuring out what it meant and when it applied. And even the most cursory tabulation of dates would have revealed papers at or beyond the six-year mark.

Data Colada touts the length of the committee’s report as a supposed indication of the committee’s care. That’s seriously off-base, as I’ll explain in a future piece. But with 1281 pages of space in their final report (including its many attachments), there was certainly room for the committee members to inquire, discuss, and report. They did not. There is not a single mention of the six-year rule anywhere in the report, and there is certainly no mention of the fact that under the plain language of that rule, these three papers are just too old to be investigated.

Applying the six-year rule

Of the four allegations against me, three pertain to papers I wrote over ten years ago (see row 1 in Table 1), and that were published more than eight years ago (see row 3 in Table 1). Table 1 indicates when I submitted the first version for peer review, when the paper was accepted, and when the paper was published. Compare those dates to the dates when HBS first received allegations against me, when the HBS Research Integrity Officer (RIO) received them, and when HBS first notified me of those allegations. For the first three papers, depending on which dates you compare, the ranges stretch from 6 years 67 days to 11 years 75 days.

As Table 1 shows, these three papers are out of scope according to the six-year rule in the policy.

Table 1: Relevant dates for three papers at issue

* Date of online publication (if published online prior to publication in print)

(Note that the 2012 PNAS paper had been retracted by the time I learned about the allegations against my work and HBS started its investigation. Also the data for the 2012 PNAS paper was collected in July 2010; The data for the 2014 PS paper was collected in 2012; The data for the 2015 PS paper was collected in 2014.)

Skeptics may disagree with the six-year rule and how long far back a university should be permitted to investigate. But think through these questions: Of the papers you published more than six years ago, how quickly and how accurately could you find the original data? How confident would you be in knowing which file is which? How readily could you convince someone who disagreed? Fact is, long-ago research poses special barriers to both proving and disproving research misconduct. And, more importantly, it is what the policy stated.

Evaluating applicability of any exception to the six-year rule

Not every “citation” and not every “use” reopens the six-year window. So, how does one determine what qualifies? The answer lies in the words “continued or renewed the research misconduct” and “for the potential benefit of the misconduct” which set out two separate tests that both must be satisfied.

Let’s focus on citations, which are the relevant aspect of the papers in question. If the nature of the citation is such that genuinely “continued or renewed” what was done wrong in the past, and if the citation offers a material “potential benefit,” the policy claims the right to investigate that misconduct. BUT, if the citation is so lightweight that it cannot be said to have continued or renewed the past wrongdoing, or if the potential benefit of the citation is so little, then the investigation is time-barred. A weighty, extended discussion might genuinely continue, renew, and extend the underlying misconduct by increasing the likelihood that a reader turns to (and relies on) the underlying research. Conversely, a lightweight citation does no such thing.

Since these papers were more than six years old, the 2021 policy allowed the HBS committee to investigate them only pursuant to one of the “continued or renewed” exceptions. But even when considering this, three of the papers are still out of scope because my brief and lightweight self-citations did not meet the 2021 policy’s high bar for exceptions to the six-year rule.

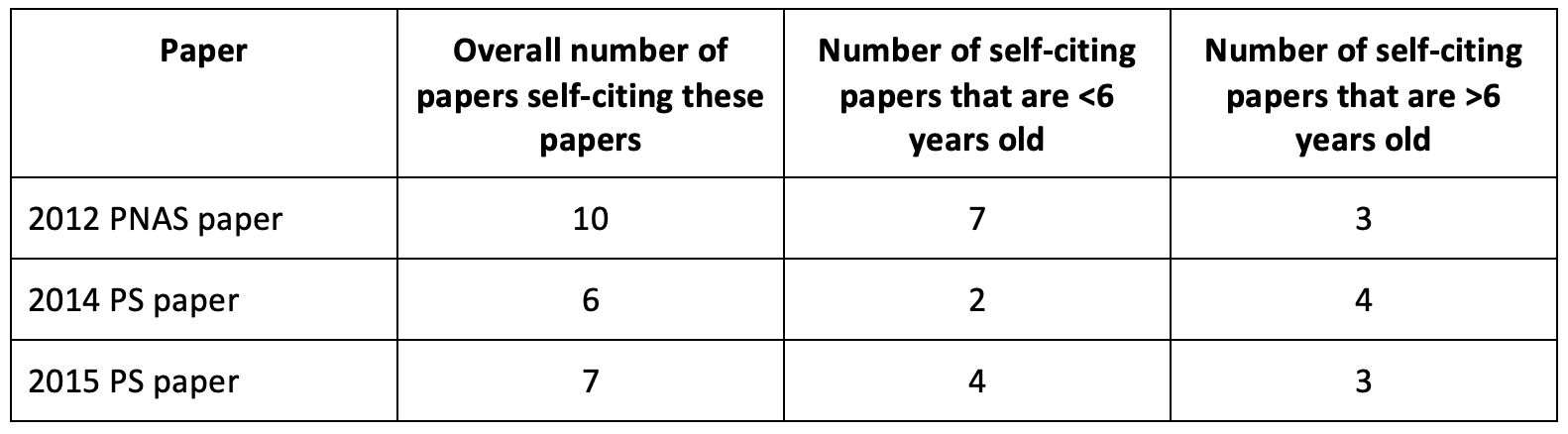

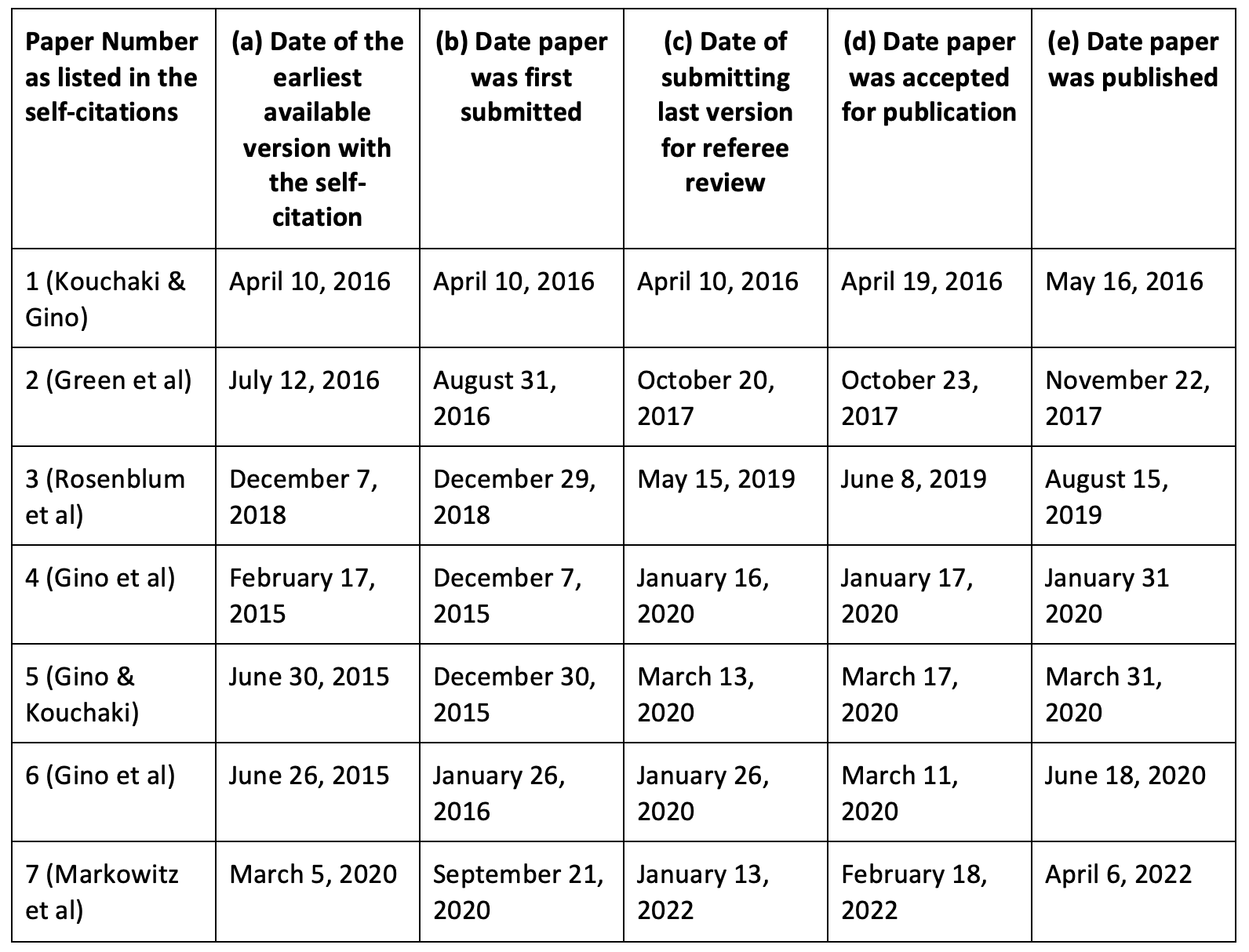

Table 2 shows my overall self-citations for these papers, calling out those citations that are less than six years old:

Table 2: Number of my papers that self-cite the three papers at issue

Methodology for Table 2: I say I “use[d]” an earlier paper A the day I wrote a citation to it in new paper B (no matter when paper B was ultimately published), as in column (a) of Table 5 (Appendix 1), Table 6 (Appendix 2) and Table 7 (Appendix 3). I prepare the right two columns consistent with the 2021 HBS policy, which calls for computing the time period between “use” of the paper and HBS receiving an allegation about that paper. I compute “<6 years old” relative to July 15, 2021, the estimated date when HBS received allegations against me.

As Table 2 shows, each of the three 2015-and-earlier papers has some self-cites that are less than six years old.

Although I self-cited all three papers, my self-citations are, on the whole, brief if not perfunctory, often offering not a single word beyond author’s name and year of publication.

I organized these 13 self-citations into logical groups, in the first column in Table 3 below. If Paper A self-cited Paper B more than once, I counted each self-citation separately. Moreover, if a self-citation belonged to multiple groups, I placed it in each applicable category. This explains why the table’s cells total considerably more than 13.

Table 3: Categorizing my recent self-citations of the three papers at issue

Consistent with the 2021 policy, this table considers only self-citations in papers I published in or after July 2015.

Every single self-citation is in at least one of categories 1 through 7. No papers are in category 8 (mentioned in a context other than 1-7). That is: Not one of my self-citations meets the criteria of the 2021 policy as to “continued or renewed” misconduct creating a “potential benefit.”

(An aside: Some might feel that 23 self-citations of three papers is a lot. I took a moment to look at other citations I made in these papers. Bottom line is my papers have many citations. Take the 2012 PNAS paper as an example. In the ten papers in which I self-cited this paper, I also cited a total of 1327 papers by others. I’m comfortable with 0.75% of my citations being self-citations. Compare a 2023 PNAS paper co-authored by a famous behavioral scientist and Nobel winner, Daniel Kahneman, for which 20% of citations were self-citations. I’m no Kahneman, but 0.75% self-citations is routine.)

The right date for evaluating self-citations

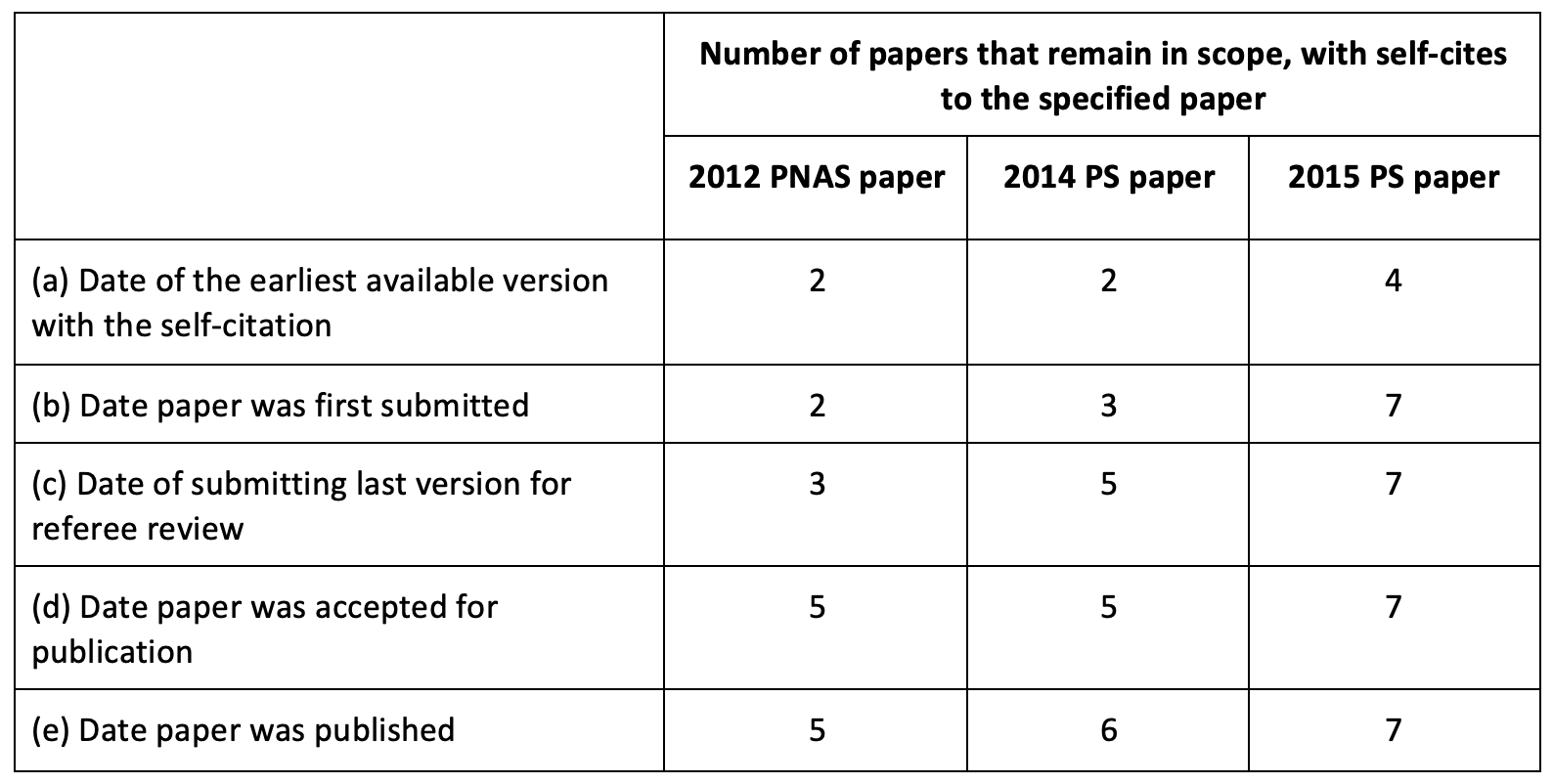

Depending on what dates are considered for self-citing papers, even fewer self-citing papers are within six years of HBS receiving allegations about my research.

The 2021 HBS policy asks whether a self-cite “continued or renewed” a given research misconduct. On what date does a self-citing paper “continue or renew” something about an allegedly-flawed prior paper? The earliest plausible date is the date on which the author wrote the words of the self-citation, and there’s a reasonable argument for using this date – this is (a) the date on which the author actually wrote the words that reference the prior paper.

But there are potential alternatives: (b) when the paper was first submitted, (c) when the paper was last submitted (i.e. last submission before acceptance), (d) when it was accepted, and even (e) when it was published. In my view each of these dates is further removed from the author's actions that “continued or renewed” any aspect of the prior paper. Table 4 summarizes how many papers remain in scope for investigation based on this careful analysis of relevant dates for the self-citing papers. Appendix 1, 2 and 3 present details supporting these values.

Table 4: Examining key dates for the self-citing papers

The categorization of self-citations and dates of self-citations interact to reduce the number of self-citing papers in scope. Depending on what date criterion a person finds most convincing, the Table 4 analysis would call for excluding certain self-citations. Of course no matter which self-citations remain, the Table 3 analysis shows that none constitute the “continued or renewed” “use for the potential benefit” required by the exception to the six-year rule.

What this all means

It is troubling that HBS and the investigation committee applied this new policy without even mentioning which clause supposedly called for going beyond the six-year rule. But under a fair reading of the 2021 policy, three of my papers were too old to be investigated under that policy.

Claiming process excellence, care, aid fairness, HBS should have looked at this in detail, and should have realized these historic papers were just too old for a careful and accurate investigation.

Some might object that it’s unfair for me to “get off” with (supposed) research misconduct on the basis of a “technicality” such as the six-year rule. Three responses to that.

I’m innocent, and I seek to prove it.

The sole impact of this rule is to limit how HBS can investigate me. Others, like Data Colada, can criticize any work they want, any time they want, without limitation by a six-year rule or anything else. If Data Colada’s attack is strong and I can’t convince readers I’m right, I suffer plenty.

The passing of time genuinely makes it more difficult both to prove misconduct and to prove innocence. These allegations pertain to papers I began working on as much as 11 years ago. So many computers, so much confusion about which file is where, so much doubt about which data was cleaned when, how, and by whom.

Those who truly care about the correctness of a proceeding – about making sure that a person found guilty is actually guilty – should want a careful, rigorous process. For centuries, legal systems have correctly judged old allegations too difficult to investigate with the required level of accuracy. That principle applies equally here.

There are likely some people I’ll never convince of my innocence. But even my toughest critic should agree that allegations about long-ago work are especially difficult to disprove. I count myself lucky that the HBS 2021 policy says such allegations are squarely out of scope.

Appendix 1 - Details of the Citation Analysis for the 2012 PNAS paper

Purpose: To evaluate whether the oldest three papers truly triggered the exception to the 6-year rule

Criteria: A self-citation is “meaningful” if it could reasonably be said to have “continued or renewed an incident of alleged research misconduct.”

A self-citation is meaningful if it does not meet any of the seven criteria in Table 3:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Mentioned in the general discussion (e.g., future directions), with no substantive discussion

Cited only in a string citation

Discussed as part of failure to replicate

Discussed in a paper that is itself only a review, not a bona fide new finding (i.e., discussed in a publication other than a peer-reviewed scholarly journal)

Discussed for only a description of a task, and not a substantive finding or methodology

Citation discusses another part of the paper, not the part subject to allegations in this proceeding

/versus/

8. Mentioned in a context that is not any of 1 through 7 above

2012 PNAS paper

Signing at the beginning makes ethics salient and decreases dishonest self-reports in comparison to signing at the end. Shu, L., Mazar, N., Gino, F., Ariely, D. & Bazerman, M. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(38), 15197-15200 (2012).

Self-citations that were published prior to July 2015:

Moore, C., & Gino, F. (2013). Ethically adrift: How others pull our moral compass from true North, and how we can fix it. Research in organizational behavior, 33, 53-77.

a. First published online 28 August, 2013

b. 336 references

Zhang, T., Gino, F., & Bazerman, M. H. (2014). Morality rebooted: Exploring simple fixes to our moral bugs. Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, 63-79.

a. First published online November 4, 2014

b. 138 references

Moore, C., & Gino, F. (2015). Approach, ability, aftermath: A psychological process framework of unethical behavior at work. The Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 235-289.

a. First published online January 1 2015

b. 272 references

Shalvi, S., Gino, F., Barkan, R., & Ayal, S. (2015). Self-serving justifications: Doing wrong and feeling moral. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(2), 125-130.

a. First published online April 6, 2015

b. 39 references

Sezer, O., Gino, F., & Bazerman, M. H. (2015). Ethical blind spots: Explaining unintentional unethical behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 77-81.

a. First published online May 1 2015

b. 63 references

Self-citations that were published in or after July 2015:

Ayal, S., Gino, F., Barkan, R., & Ariely, D. (2015). Three principles to REVISE people’s unethical behavior. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(6), 738-741.

a. First published online November 17, 2015

b. 26 references

Hildreth, J. A. D., Gino, F., & Bazerman, M. (2016). Blind loyalty? When group loyalty makes us see evil or engage in it. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 132, 16-36.

a. First published online December 17, 2015

b. 175 references

Hauser, O. P., Gino, F., & Norton, M. I. (2018). Budging beliefs, nudging behaviour. Mind & Society, 17, 15-26.

a. First published online March 13, 2019

b. 57 references

Zhang, T., Gino, F., & Margolis, J. D. (2018). Does “could” lead to good? On the road to moral insight. Academy of Management Journal, 61(3), 857-895.

a. First published online June 22, 2018

b. 206 references

Kristal, A. S., Whillans, A. V., Bazerman, M. H., Gino, F., Shu, L. L., Mazar, N., & Ariely, D. (2020). Signing at the beginning versus at the end does not decrease dishonesty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(13), 7103-7107.

a. First published online March 31, 2020

b. 15 references

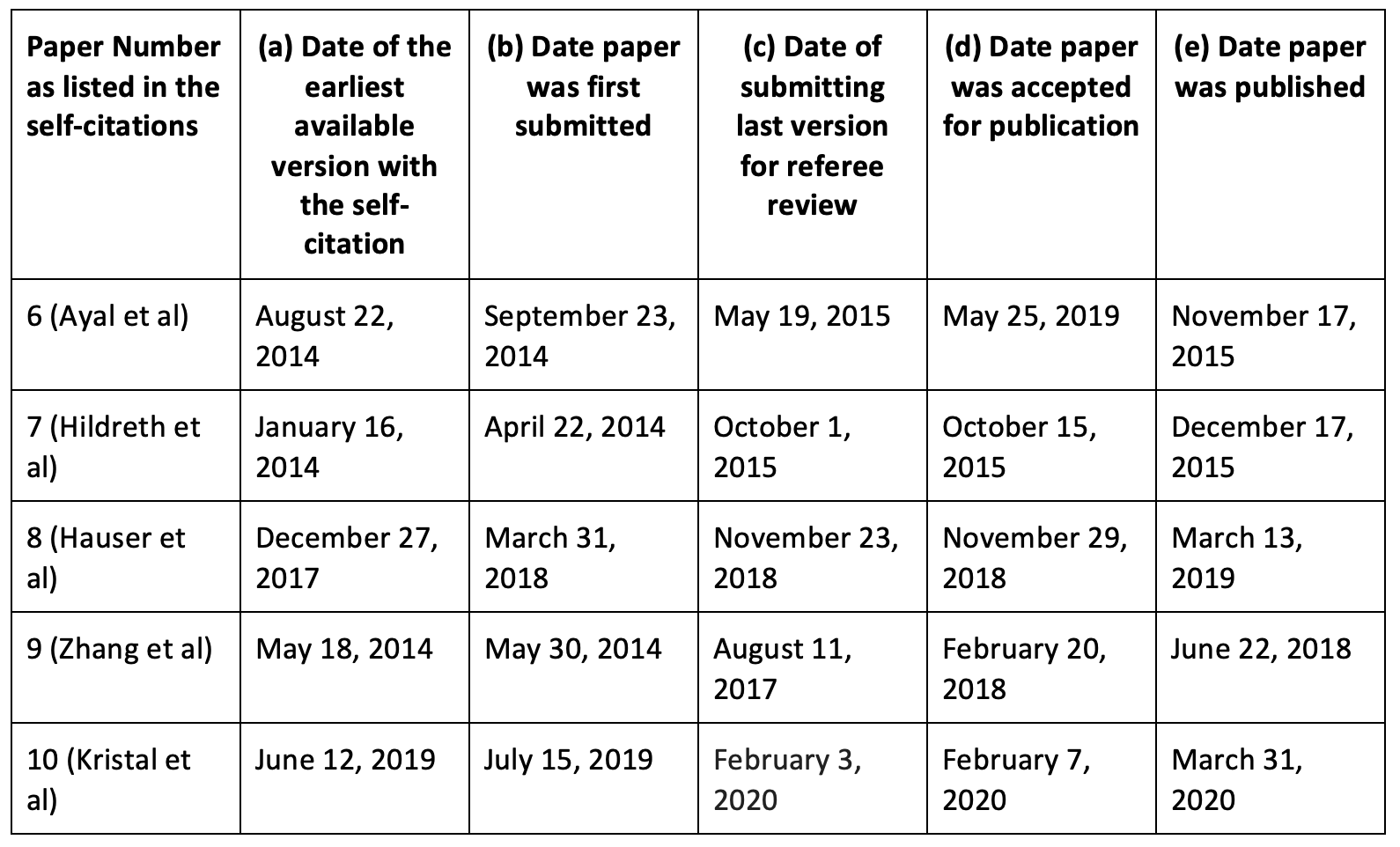

Table 5. Analysis of papers (self-citations) published in or after July 2015

Using criterion (d) puts one self-cite out of scope, if the date HBS “received” the allegation is deemed to be one week before when HBS told me about the allegation. (This approach would follow the 2021 policy instruction that the Research Integrity Officer “must” notify the respondent “at the time of or before beginning an inquiry” which, the policy says, is “preferably” “within a week” of receiving an allegation. Since the RIO first told me about the allegation on October 27, 2015, the allegation could be deemed received on October 20, 2015 – with HBS, not me, bearing the cost of HBS’s apparent delay in notifying me.) Using criterion (c) puts two self-cites out of scope. Using criterion (a) or (b) puts three self-cites out of scope and leaves just two self-cites as the potential basis for investigating this paper.

Details of self-citations for papers published in or after July 2015:

Ayal et al

This is a short, 5-page review paper (no data). The paper is cited when referring to the field study in the paper (not the lab study in question in the allegations): “In a field study that exemplifies the effectiveness of this principle, researchers collaborated with an automobile insurance company that hoped to encourage people to report the true mileage on their cars. Of course, higher mileage leads to a higher premium; therefore people save money by lying and under-reporting. In this study, customers were asked to sign a statement declaring they were telling the truth. Importantly, the researchers randomly assigned customers to a ‘regular’ statement where their signature was placed at the bottom of the page (after reporting the car mileage), or a ‘Self-Engagement’ statement, where their signature was placed at the top of the page (before reporting the car mileage). This subtle difference had an impressive

effect: when people signed their names at the top of the page they reported more mileage (Shu et al., 2012).”

Why it does not count:

Discussed in a paper that is itself only a review, not a bona fide new finding (i.e., discussed in a publication other than a peer-reviewed scholarly journal)

Citation discusses another part of the paper, not the part subject to allegations in this proceeding

Hildreth et al

This paper cites the paper for the task used, on page 25: “Participants completed a measure of ethical salience (adapted from Shu, Mazar, Gino, Ariely, & Bazerman, 2012).”

Why it does not count:

Discussed for only a description of a task, and not a substantive finding or methodology

Hauser et al

This paper cites the paper as an example of a broader point (p. 20): “For instance, evidence that context matters can be illustrated with a highly successful nudge: Shu et al. (2012) demonstrate that placing a signature box at the top of a form highlights an ethical “self-image” and reduced cheating on the form subsequently.”

Why it does not count:

Discussed in a paper that is itself only a review, not a bona fide new finding (i.e., discussed in a publication other than a peer-reviewed scholarly journal)

Zhang et al

The paper is cited in the General Discussion as part of a broader point (p. 878): “More recently, the field has examined the impact of tools to help employees and managers make more ethical decisions when facing temptations to cheat (Gino & Margolis, 2011; Moore & Gino, 2013; Shu, Mazar, Gino, Ariely, & Bazerman, 2012).”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the general discussion (e.g., future directions), with no substantive discussion

Cited in a string citation, without discussion of substantive finding

Kristal et al - 11 different self-cites

This is the paper that fails to replicate the 2012 paper.

“Five of the seven authors of this manuscript conducted research published in PNAS (Shu et al., 2012), showing that signing a veracity statement at the beginning of a tax form (in two small-sample laboratory studies) as well as an insurance audit form (in a field experiment), as opposed to the standard procedure of signing it at the end of the form, decreases dishonest reporting of personal information.”

“As a consequence of these null effects, together with the original authors of the PNAS paper, the authors then set out to conduct a direct replication of the first laboratory experiment described in the PNAS paper (Shu et al., 2012).”

“To test this hypothesis in the original PNAS paper (Shu et al., 2012), there were two laboratory experiments (n = 101 and n = 60, respectively) and one field experiment (n = 13,488).”

“Consistent with the stated hypothesis, in these two laboratory studies (Shu et al., 2012), fewer participants cheated (2), they claimed more accurate performances, and (3) claimed fewer expenses (likely due to more honest reporting of their expenses) when the veracity statement that they were asked to sign was placed at the top of the tax form (vs. at the bottom).”

“Studies 1–5 were intended to study whether online cheating could be reduced by asking people to provide an online signature before versus after reporting, rather than the goal of providing a replication, and as a result, these studies did not include the identical methods that were originally used in the PNAS paper (Shu et al., 2012).”

[3 self-cites] “While all studies were incentive-compatible, these new studies used forms where there was not necessarily an established norm for providing a signature at the bottom and no cost for dishonesty, whereas the Shu et al. (2012) experiments included tax and audit forms where people typically expect to provide their signature at the end and would risk punishment for dishonesty. Thus, in study 6, we conducted a direct replication of study 1 of the PNAS (Shu et al., 2012) manuscript (leaving out the pure control condition: no signature), given that it was the most tightly controlled laboratory experiment and it produced the largest effect size for percent of people overclaiming their performance income (d = 0.70) (Shu et al., 2012).”

“Whereas the original PNAS findings show that having the veracity statement that people are asked to sign at the beginning promotes honesty (Shu et al, 2012), in the new study 1, there was no difference in the average performance reporting across conditions.”

“In the original PNAS paper, across two laboratory experiments (n = 161), the authors found that asking participants to sign a veracity statement placed at the top of a tax form increased honest responding as compared to at the end of the tax form (Shu et al., 2012).”

“While we have two examples (one from Shu et al. (2012) and one from this paper [study 1]) failing to find a difference between signing at the bottom or no signature, we do not have enough evidence to make claims in the current paper about the effect of signing versus not signing at all.”

Why it does not count:

Discussed as part of failure to replicate

Appendix 2 - Details of the Citation Analysis for the 2014 PS paper

2014 PS paper

Evil genius? How dishonesty can lead to greater creativity. Gino, F. & Wiltermuth, S. Psychological Science, 25(4), 973-981 (2014).

Self-citations that were published prior to July 2015:

None

Self-citations that were published in or after July 2015:

Huang, L., Gino, F., & Galinsky, A. D. (2015). The highest form of intelligence: Sarcasm increases creativity for both expressers and recipients. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 131, 162-177.

a. First published online July 17, 2015

Kouchaki, M., & Gino, F. (2016). Memories of unethical actions become obfuscated over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(22), 6166-6171.

a. First published online May 16, 2016

Gino, F. (2016). How moral flexibility constrains our moral compass. J.-W. van Prooijen & PAM van Lange (Eds.), Cheating, corruption, and concealment: The roots of dishonesty, 75-97.

a. First published online June 5, 2016

Lu, J. G., Quoidbach, J., Gino, F., Chakroff, A., Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2017). The dark side of going abroad: How broad foreign experiences increase immoral behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 112(1), 1.

a. Published in print in January 2017. First published online between October 6, 2016 (when the paper was accepted) and January 1, 2017.

Wiltermuth, S. S., Vincent, L. C., & Gino, F. (2017). Creativity in unethical behavior attenuates condemnation and breeds social contagion when transgressions seem to create little harm. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 139, 106-126.

a. First published online February 9, 2017

Zhang, T., Gino, F., & Margolis, J. D. (2018). Does “could” lead to good? On the road to moral insight. Academy of Management Journal, 61(3), 857-895.

a. First published online June 22, 2018

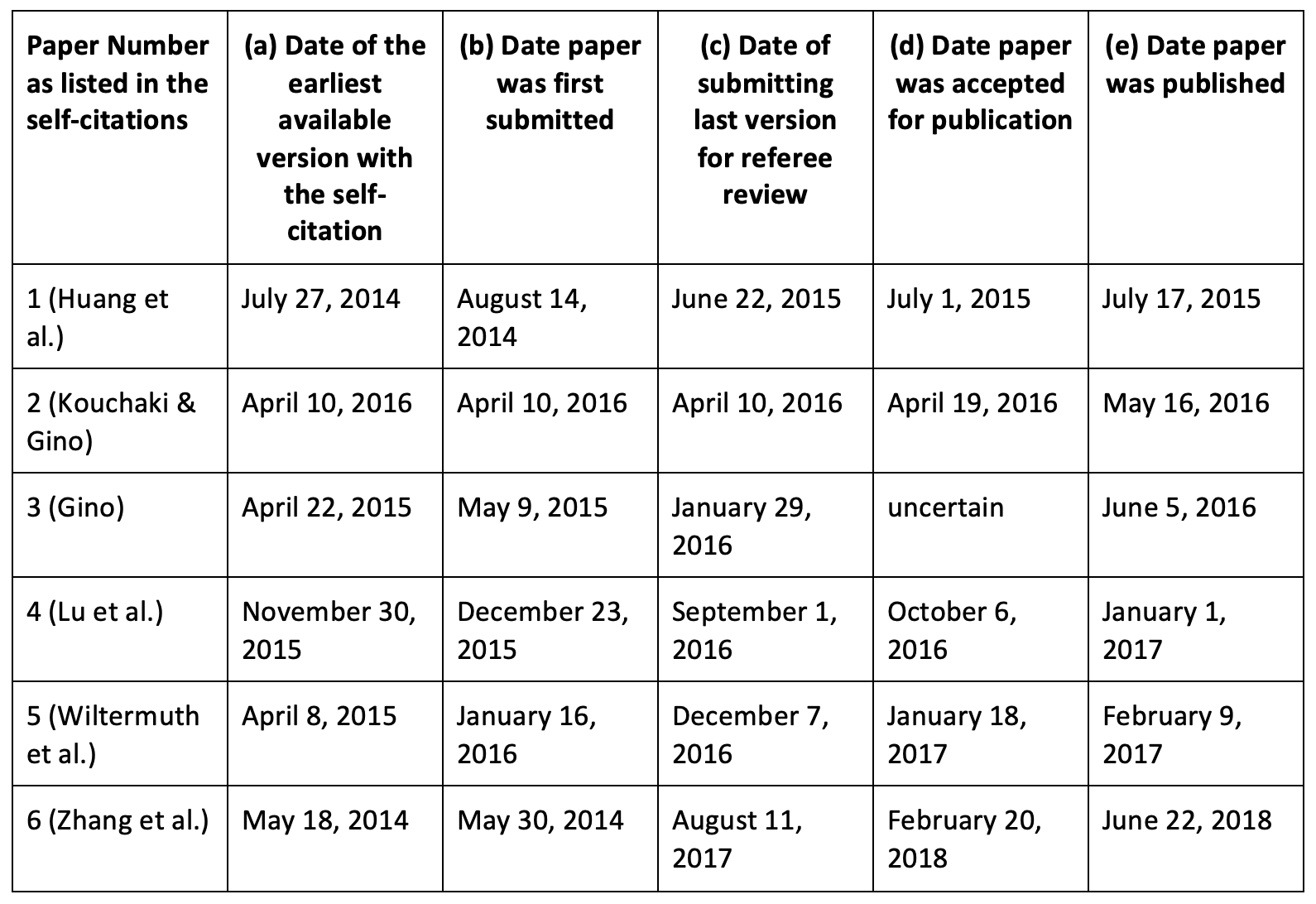

Table 6. Analysis of papers (self-citations) published in or after July 2015

Under criterion (c) or (d), one self-cite is out of scope. Using criterion (b), three self-cites are out of scope. Using criterion (a) puts four self-cites out of scope and leaves just two self-cites as the potential basis for investigating this paper.

Details of self-citations analysis for papers published in or after July 2015:

Huang et al

The paper is cited in the Supplemental Information in the description of one of the studies (p. 5 of SI): “At time 1, participants played a die-throwing game (as in Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014).”

Why it does not count:

Discussed for only a description of a task, and not a substantive finding or methodology

Kouchaki & Gino

The paper is cited in the General Discussion as part of a broader point (p. 174): “Second, our research corroborates the increasingly robust relationship between various forms of contradiction and creativity (e.g., Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014; Huang & Galinsky, 2011).”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the general discussion (e.g., future directions), with no substantive discussion

Cited in a string citation, without discussion of substantive finding

Gino

The paper is cited as part of a point made in that paper (p. 86): “As noted by Gino and Wiltermuth (2014), both creativity and unethical behavior involve rule breaking.”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Lu et al – 2 different self-cites

The paper is cited in the Introduction before Study 8, to make a broader point: “Given that foreign experiences can enhance creativity (e.g., Maddux & Galinsky, 2009), and that creativity can be positively associated with immoral behavior (Gino & Ariely, 2012; Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014), it is possible that creativity also contributes to our proposed effect.”

And then again among other papers for the task used: “Next, participants performed a number-search matrix task (developed by Mazar, Amir, & Ariely, 2008; see also Gino & Ariely, 2012; Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014; Vincent, Emich, & Goncalo, 2013).”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Cited in a string citation, without discussion of substantive finding

Discussed for only a description of a task, and not a substantive finding or methodology

Wiltermuth et al

The paper is cited in the General Discussion as part of a broader point (p. 123): “The work complements other work documenting how creativity can increase the odds that an individual will behave unethically (e.g., Gino & Ariely, 2012; Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014) by showing that one actor’s creativity may also have an effect on other actors’ likelihoods of behaving unethically.”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the general discussion (e.g., future directions), with no substantive discussion

Cited in a string citation, without discussion of substantive finding

Zhang et al

The paper is cited in Table 1 (p. 858) which summarizes the literature. The paper is mentioned among dozens of others as an example of a paper analyzing “right vs wrong” dilemmas. And then as part of a broader point (p. 859): “Yet, to date, research has found an inverse relationship between creativity and ethicality (Gino & Ariely, 2012; Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014).” Finally, it is cited in the General Discussion section (p. 879): “Additionally, our findings contribute to research on the link between creativity and ethics (Baucus, Norton, Baucus, & Human, 2008; Gino & Ariely, 2012; Gino & Wiltermuth, 2014; Kelly & Littman, 2001; Vincent & Kouchaki, 2016; Wang, 2011).”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Cited in a string citation, without discussion of substantive finding

Appendix 3 - Details of the Citation Analysis for the 2015 PS paper

2015 PS paper

The moral virtue of authenticity: How inauthenticity produces feelings of immorality and impurity. Gino, F., Kouchaki, M., & Galinsky, A. D. Psychological Science, 26(7), 983-996 (2015).

Self-citations that were published prior to July 2015:

None

Self-citations that were published in or after July 2015:

Kouchaki, M., & Gino, F. (2016). Memories of unethical actions become obfuscated over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(22), 6166-6171.

a. First published online May 16, 2016

Green Jr, P. I., Finkel, E. J., Fitzsimons, G. M., & Gino, F. (2017). The energizing nature of work engagement: Toward a new need-based theory of work motivation. Research in Organizational behavior, 37, 1-18.

a. First published online November 22, 2017

Rosenblum, M., Schroeder, J., & Gino, F. (2020). Tell it like it is: When politically incorrect language promotes authenticity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(1), 75.

a. First published online August 15, 2019

Gino, F., Sezer, O., & Huang, L. (2020). To be or not to be your authentic self? Catering to others’ preferences hinders performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 158, 83-100.

a. First published online January 31, 2020

Gino, F., & Kouchaki, M. (2020). Feeling authentic serves as a buffer against rejection. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 160, 36-50.

a. First published online March 31, 2020

Gino, F., Kouchaki, M., & Casciaro, T. (2020). Why connect? Moral consequences of networking with a promotion or prevention focus. Journal of personality and social psychology, 119(6), 1221.

a. First published online June 18, 2020

Markowitz, D. M., Kouchaki, M., Gino, F., Hancock, J. T., & Boyd, R. L. (2023). Authentic First Impressions Relate to Interpersonal, Social, and Entrepreneurial Success. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(2), 107-116.

a. First published online April 6, 2022

Table 7. Analysis of papers (self-citations) published in or after July 2015

Criterion (a) puts three self-cites out of scope, and leaves just four self-cites as the potential basis for investigating this paper.

Details of self-citations analysis for papers published in or after July 2015:

Kouchaki & GIno

The paper is cited in the Supplemental Information in the description of one of the studies, for one of the measures (p. 5 of SI): “To assess participants’ moral self-concept, we asked them to use a seven-point scale (from 1 = not at all to 7 = to a great extent) to indicate the extent to which they felt each of the following: moral, generous, cooperative, helpful, loyal to others, dependable, trustworthy, reliable, caring, and respectful (α = 0.96) (Gino, Kouchaki, & Galinsky, 2015).”

Why it does not count:

Discussed for only a description of a task, and not a substantive finding or methodology

Green et al

This is a review paper that cites the paper in question towards the end, as follows (p. 13): “People who suppress their authentic selves in deference to organizational structures feel alienated from the self (Grandey, 2003; Roberts, 2012), can be exhausted by the cognitive effort associated with suppressing the self (Hewlin, 2003, 2009), and can even experience a sense of immorality and impurity resulting from a sense that they are being untruthful with their self (Gino, Kouchaki, & Galinsky, 2015).”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the general discussion (e.g., future directions), with no substantive discussion

Rosenblum et al

The paper is cited in the theory development: “First, one possibility is that, because ideological groups utilize different moral foundations (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt, Graham, & Joseph, 2009), liberals care more about harm/care and therefore may be particularly sensitive to political incorrectness seeming harmful, whereas conservatives care more about purity, which is linked to authenticity (Gino, Kouchaki, & Galinsky, 2015) and therefore may be particularly sensitive to political incorrectness seeming authentic.

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Gino, Sezer, & Huang – 2 different self-citations

The paper is cited in the Introduction as part of a broader point: “When people behave inauthentically by straying from what they consider to be their true self, they experience psychological discomfort (Gino, Kouchaki, & Galinsky, 2015).” It is then cited again in the theory development: “Trying to match others’ preferences and interests rather than expressing one’s own is a form of inauthenticity, especially when the two differ and are not aligned, and inauthenticity heightens psychological discomfort (Gino et al., 2015).”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Gino & Kouchaki – 5 different self-citations

The paper is cited in the theory development (p. 37) as part of a broader point: “People are more likely to feel authentic when they engage in positive behaviors, as state authenticity taps into a moral and positive sense of self (Newman, Bloom, & Knobe, 2014). Inauthentic experiences, instead, make people feel less moral and heighten their motivation to reaffirm their self-integrity (Gino, Kouchaki, & Galinsky, 2015; Jongman-Sereno & Leary, 2016).”

The paper is also cited on page 38 on how to manipulate authenticity: “Most prior experimental research on the effects of state authenticity on various outcomes has employed a writing manipulation to trigger feelings of authenticity in the moment, which has been found to be effective (Gino et al., 2015; Kifer et al., 2013).”

Finally, it is cited when explaining the writing task used in one of the studies

(p. 39): “Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: authenticity vs. inauthenticity vs. control. In the authenticity [inauthenticity] condition, the instructions to the recall and writing task read (as in Gino et al., 2015): [...]”

(same page): “Participants in the neutral condition instead were asked to recall and write about a neutral experience, namely how they spend their evenings, and were asked to describe a typical instance (as in Gino et al., 2015).”

(p. 42): “Next, as a manipulation check for our authenticity manipulation, we asked participants to answer a few questions about the wristband. In particular, they indicated their agreement with four statements (adapted from Gino et al., 2015): [...]”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Cited in a string citation, without discussion of substantive finding

Discussed for only a description of a task, and not a substantive finding or methodology

Gino, Kouchaki, & Casciaro – 4 different self-citations

The paper is cited in the theory development (p. 1223): “The moral psychological foundations of this association between regulatory focus and subjective authenticity are further corroborated by theory and evidence that people experience feelings of authenticity as moral and pure; conversely, feelings of inauthenticity are experienced as immoral and impure (Gino, Kouchaki, & Galinsky, 2015).”

And then again, on the same page (p. 1223): “Specifically, a promotion focus may yield networking concerned with authentic virtues and meeting one’s ethical ideal, and a prevention focus may yield networking motivated by the “shoulds” prevailing in one’s professional environment and thus triggers feelings of inauthenticity and impurity (Gino et al., 2015).”

It is also mentioned in the task of Study 2 (p. 1227): “Using the same scale, they also indicated how much they felt dirty, inauthentic, and impure (as in Gino et al., 2015) to assess feelings of moral impurity.”

And finally it is mentioned in the General Discussion section (p. 1235): “Prior work has shown that authenticity is experienced as a moral state (Gino et al., 2015)”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion

Mentioned in the general discussion (e.g., future directions), with no substantive discussion

Discussed for only a description of a task, and not a substantive finding or methodology

Markowitz et al

The paper is cited in the Introduction as part of a broader point (p. 107): “Perceptions of authenticity are linked to positive outcomes across a variety of domains, including hospitality (Grandey et al., 2005), morality (Gino et al., 2015), medicine (Arnason, 1994), and academia (Archer, 2008).”

Why it does not count:

Mentioned in the literature review, with no substantive discussion